Years of Living Dangerously: Indonesians Are Smoking More and More

In most of the Western world, smoking a cigarette, anywhere, has become a risky proposition. Not only does a smoker have to contend with the graphic, unsettling images on their pack depicting the dire, physical consequences of cigarette smoking, they are also, literally, forced outside.

But, no one weeps for how bad smokers have it. Smoking kills, it says so right on the pack. Only, we have come a long way from cigarettes, and smoking culture, in general, being held in high regard as something not only normal but healthy and good for you to the very bane of human existence.

This sea change in attitudes toward smoking, heralded by medical and scientific evidence definitively proving a link between smoking and cancer-related illnesses, has caused worldwide smoking rates to drop over time.

In the United States alone, the peak smoking rate of 45% of Americans in the 1950s has dropped to just 15% in the 2000s. And worldwide, the overall rate of current, regular smokers has fallen to 20% in 2015, from 27% in 2000.

One country, however, has seemingly gone untouched not only by anti-smoking campaigns but also by the negative public opinion attached to smoking common in other parts of the world. That country is Indonesia.

Table Of Contents

A Confluence of Factors

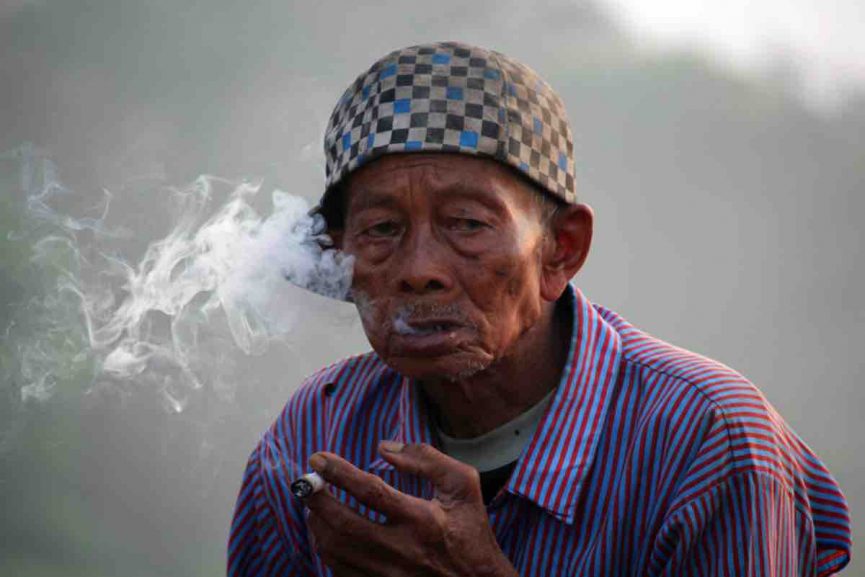

The statistics say it all. In 2000, the percentage of Indonesian men who smoked was 56%. In 2017, that number was 76%. And it’s men, mostly, who are responsible for such high figures since the percentage of Indonesian women smokers is only 4% and steadily falling.

This sharp increase in the number of male Indonesian smokers would inspire intense curiosity from anyone: why are more Indonesian men smoking while the rest of the world is quitting? The answer has as much to do with international economic policy, and trade regulations than it does with the unique cultural history of Indonesia.

It could even be argued that it was the intense and unrelenting anti-smoking campaign in the West that inspired so many to quit smoking that drove up the number of new smokers in Indonesia.

With that said, we still have to go all the way back to the decision to deregulate the Indonesian tobacco market as the catalyst that resulted in so many Indonesian men taking up smoking.

Free Trade, Free Reign

Economic liberalization was all the rage in the early 1990s. In 1994, Canada, the United States, and Mexico had just signed NAFTA (North American Free Trade Agreement) that opened the borders to the free flow of goods and products across their respective borders. This event presaged the opening of international trade around the world.

Indonesia, then under the leadership of the military strongman Suharto, freely opened its markets to Western companies looking to increase profits and lower costs, especially labor costs, by operating in developing countries.

Tobacco companies were among the first to pounce on the Indonesian cigarette market. The two giants of international tobacco, Philip Morris International, and British American Tobacco, wasted no time making inroads into the once-protected Indonesian marketplace.

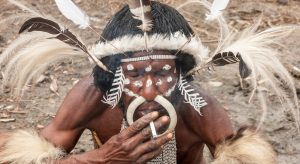

After their more mainstream tobacco products and brands were met with a tepid response from Indonesian smokers, the two multinationals realized the potential of mass-producing and marketing a tobacco product that a majority of Indonesians were already familiar with: kretek.

Only in Indonesia

Kretek, or a clove cigarette, is the Indonesian variant of a traditional cigarette. Cloves and other potpourri are mixed in with tobacco and then rolled up and smoked just like a cigarette.

The burning of the cloves inside reduces the initial harshness of tobacco smoke, making them easier and more pleasurable to smoke than factory-produced cigarettes. But the cloves emit their brand of a toxic chemical, known as eugenol when burned and kreteks are no less safe than other tobacco cigarettes.

PMI and BAT knew all this, and with their purchase of local manufacturers of kreteks, they sought to expand and maintain their grip on the Indonesian tobacco market. This expansion was aided by the complete absence of a regulatory regime to police the marketing and selling of cigarettes, which so hampered tobacco companies in other countries like the United States.

With the freedom to market and sell their products to anyone, even children, the two companies wasted no time integrating their brand into everyday Indonesian life. This freedom has meant that Philip Morris and British American Tobacco sponsored cultural and sporting events.

Philip Morris and British American Tobacco also started to nakedly and unscrupulously create brands and products specifically for young people. Kretek brands like Marlboro Mix 9 and established brands like A Mild, were directly marketed to (mostly) young men.

These campaigns, through their marketing techniques, equated cigarettes and smoking with heightened masculinity and vigor. And, as a result, we see the astronomical jump in male smokers in Indonesia.

The Wild, Wild East

In the early 90s, tobacco companies, like actual smokers, were getting pushed to the margins. Lawsuit after lawsuit, finding after finding that proved smoking was a cause of cancer, left them little choice but to relocate.

Countries like Indonesia, with a developing economy and a decidedly pro-business mindset, were the perfect places for multinational companies like Philip Morris and British American Tobacco to find safe haven.

In Indonesia, tobacco companies could operate without any government oversight. And they did act as if no one was looking. They co-opted a local custom for mass-production and aggressively marketed these new products to all members of the public backed by typical exaggeration and dubious health claims.

The result was Indonesia being pushed back to a time when smoking cigarettes was viewed as a manly, and worthwhile pursuit, instead of as the unhealthy, potentially lethal habit that we all know it to be.

Comments

Leave a comment